Cyber Safety in Construction

It’s all just #Safety – the next evolution of safety culture

Health and Safety in the workplace has undergone a profound transformation in British business culture over the past two centuries. What was once a fringe concern – often viewed as a burdensome compliance matter – is today embraced as a fundamental corporate value ingrained in daily operations. Nowhere is this evolution more evident than in the UK construction sector, historically one of the most hazardous industries.

Over time, major accidents and public outcry spurred landmark regulations that gradually shifted safety from an afterthought to a core organizing principle. As one business commentator observed, “businesses eventually realised health and safety benefited their bottom line” , leading to safety becoming not just a legal obligation but a key performance metric and ethical commitment. This research explores that journey: from the historical struggles for basic worker protection, through the rise of proactive safety culture (embodied in initiatives like “See Something, Say Something”), to the broadening definition of “safety” to include mental well-being and even cybersecurity. It examines how physical safety, psychological health, and cyber resilience are increasingly viewed as interrelated facets of a holistic safety culture. Expert opinions, statistics, and case studies will illustrate how UK organisations – especially in construction – have integrated these dimensions, and evaluate whether a unified approach to safety (encompassing physical, mental, and digital realms) is the future oforganisational excellence.

Historical Overview: From Perilous Workplaces to Regulatory Landmarks

Early Industrial Era – “Safety” on the Fringe: In the 19th century, Britain’s rapid industrial and infrastructural expansion came at a tremendous human cost. Construction and engineering projects were often deadly, with minimal protections for workers. A stark example is the building of the railways: roughly “three workers died for every mile of track laid” in the mid-1800s. On one notorious project – the Woodhead Tunnel (1840s) between Manchester and Sheffield – 32 workers were killed and 140 seriously injured during six years of construction. Shockingly, an additional 28 workers’ family members died from cholera due to the squalid camp conditions. This calamity, publicized by social reformer Edwin Chadwick, revealed that the death rate for those tunnel workers “was worse than for soldiers fighting at the Battle of Waterloo,” prompting public outrage and a government inquiry. The ensuing reforms placed responsibility on rail companies for workers’ health, welfare, and living conditions – one of the earliest recognitions that employers must actively safeguard their workforce. Throughout the 1800s and early 1900s, such incidents and campaigning slowly led to piecemeal legislation (e.g. the Factory Acts) to curb the worst dangers of industrial work . However, progress was sluggish and enforcement weak; even by the mid-20th century, construction sites remained perilous with safety largely a secondary concern.

British Safety Council “Hard Hats Protect” poster from the 1980s. In the early years of modern health and safety law, campaigns like this were used to instil a safety consciousness on construction sites, emphasizing simple protective measures (Courtesy of British Safety Council)

1970s – A Turning Point with the Health and Safety at Work Act: Workplace safety culture in Britain truly began to shift from the “fringe” to the mainstream with a watershed reform in 1974. In that year – against a backdrop of still-alarming accident rates – the government passed the Health and Safety at Work etc. Act 1974, which overhauled antiquated safety laws. The Act was revolutionary in that it extended duty of care to virtually all workplaces and all persons (including employees, contractors and the public), and it established the Health and Safety Executive (HSE) as a national regulator. Crucially, it introduced a more proactive, goal-setting approach: instead of narrowly prescriptive rules, employers now had a broad responsibility to ensure “so far as is reasonably practicable” the health, safety, and welfare of all their employees. This change encouraged businesses to develop internal safety management systems and think of safety as an ongoing process rather than just minimal legal compliance. The urgency of the reform is clear from the statistics of the era: in 1974, 166 construction workers were killed on the job, accounting for roughly a quarter of all workplace deaths in Britain that year. Such grim figures underscored why a new approach was needed. Following the Act’s introduction, the late 1970s and 1980s saw numerous campaigns (many led by the British Safety Council and trade unions) to change attitudes on sites. For example, basic personal protective equipment like hard hats – seldom worn on sites even in the early 1980s – became increasingly enforced by decade’s end.

Landmark Incidents Driving Change: While the 1974 Act provided a framework, it was often major disasters that spurred specific regulations and cemented safety as a boardroom concern. In 1973, just prior to the Act, the collapse of a cooling tower during construction in Scunthorpe killed 5 workers, highlighting the need for better oversight of engineering methods. A year later, the Flixborough chemical plant explosion (1974, 28 killed) – though in the process industry – prompted the UK to strengthen process safety and influenced EU industrial safety directives. Later, the Piper Alpha offshore oil platform explosion in 1988 (167 fatalities) was a seminal event that introduced the concept of “safety culture” into the corporate lexicon. The public inquiry by Lord Cullen into Piper Alpha exposed catastrophic management failings and a lack of safety leadership, leading to sweeping changes in offshore regulations and an industry-wide recognition that an ingrained safety culture (not just procedures on paper) was essential to prevent such tragedies. In construction, the collapse of London’s Ronan Point tower in 1968 (a partial building collapse due to a gas explosion) had earlier led to tightened building regulations on structural integrity. More recently, the tragic Grenfell Tower fire of 2017 (which killed 72 residents) has forced the construction and real-estate sector to confront fire safety and accountability in building design and refurbishment – resulting in the Building Safety Act 2022 and new regulator regimes for building safety. Each of these incidents, while in different domains, contributed to an emerging consensus that safety must be systematic and prioritized from the highest levels of management. By the 1990s, regulations specific to construction safety management were introduced, notably the Construction (Design and Management) Regulations (first in 1994, updated in 2007 and 2015). The CDM regulations placed legal duties on not just contractors but also clients and designers to plan for safety – a radical idea that safety should be “designed in” to projects from the start, rather than addressed reactively.

Dramatic Improvements: The cumulative impact of stronger regulation and changing attitudes has been a dramatic long-term decline in injuries and fatalities in UK construction. In 1981 (seven years after the Act), there were still 116 construction worker deaths – but this was already ~50 fewer than in 1974. Fast-forward to recent years, and annual construction fatalities have fallen to a few dozen, despite a larger workforce. In 2022/23, for example, 45 construction deaths were recorded (out of 135 work-related fatalities across all industries) – a tragic number, but a fraction of the toll in earlier decades. The fatal injury rate in construction has dropped to around 2 per 100,000 workers, which while still about four times higher than the all-industry average, is vastly safer than the double-digit rates of the past. The UK now boasts one of the lowest rates of work-related fatalities and injuries in Europe, a fact often credited to its robust regulatory regime and improvements in safety management. In the words of the HSE, since its formation “workplace fatalities have decreased by 85%” and injuries by over 70% in the decades after 1974 – an extraordinary change. This historical progress sets the stage for examining how safety grew from a perfunctory compliance issue into a core value and culture within organisations.

From Compliance to Culture: Embedding Safety as a Core Value

The Rise of Safety Culture: By the late 20th century, leading British firms in construction and other sectors began to realize that simply having safety rules was not enough – what mattered was fostering a “safety culture.” The term safety culture gained prominence after analyses of disasters (like Piper Alpha and Chernobyl) showed that deeper organisational attitudes and behaviours were at fault. A positive safety culture means safety is a shared value at all levels: management demonstrates commitment, and employees feel responsible for not only their own safety but their co-workers’. In practical terms, this cultural shift was evident as companies moved from reactive compliance (checking the box on regulations) to proactive prevention – conducting risk assessments, encouraging near-miss reporting, and continuously training staff. Many large UK contractors adopted slogans like “Goal Zero” or “Everyone Home Safe” to signal a zero-tolerance approach to accidents. Corporate leadership became visibly involved: for instance, at ACCO Brands (a manufacturing firm with UK operations), the global chairman personally attends every lost-time accident review meeting, underscoring that safety is managed from the boardroom down. Such top-level engagement sends a clear message that safety is fundamental to business success, not an afterthought. Indeed, evidence mounted that good safety performance correlates with good quality and productivity, whereas poor safety is enormously costly (through lost workdays, insurance, legal penalties, etc.). Over time, many British businesses came to agree that “sending workers home safe and well each day” is an essential part of operations – an ethical imperative and a contributor to the bottom line. It is now common to see Safety listed as a core value in mission statements and to find boards reviewing safety KPIs (like accident rates) alongside financial metrics.

“See Something, Say Something” – Reporting Without Fear: A cornerstone of an effective safety culture is that employees at all levels feel empowered to speak up about hazards, near misses, and unsafe behaviours without fear of reprisal. This marks a sea change from decades past, when workers often stayed silent about risks to avoid blame or job consequences. Organisations in the UK have increasingly adopted open reporting initiatives, encapsulated by the motto “See Something, Say Something.” For example, in 2012 ACCO Brands rolled out a company-wide “See Something, Say Something” program to encourage all staff – from junior employees to senior managers – to call out unsafe conditions or acts. The idea, as safety manager Lee King explains, is that “the most junior person [should be able to tell] the most senior person that they’re doing something unsafe, without ramifications.”. By explicitly removing the fear of punishment or “shooting the messenger,” such programs aim to surface small problems before they become big accidents. It is admittedly challenging to overcome hierarchical barriers – as King noted, in most organisations it’s “very difficult to direct criticism upward” – but over time these efforts can shift norms. ACCO found that initially workers were hesitant to raise safety concerns, but as managers responded in a “relaxed” and constructive manner (avoiding any name-and-shame), employee feedback increased year by year. This openness is key to a learning culture: investigations of near misses and minor incidents provide valuable lessons to prevent serious accidents. The UK construction industry in particular has embraced near-miss reporting; many sites have anonymous hazard reporting cards or smartphone apps, making it easy for a worker to flag, say, a wobbly scaffold or a lapse in procedure. The old adage “an accident is just the tip of the iceberg” is often cited – for every serious injury, there might be hundreds of near misses – so capturing those near misses is gold for prevention. Encouragingly, companies report that as reporting goes up, actual incidents tend to go down, showing employees are actively identifying and managing risks.

Another related concept gaining traction is “psychological safety” – the idea that workers feel safe to voice concerns or admit mistakes without humiliation or retribution. Psychological safety, as coined by experts like Amy Edmondson, is now recognized as crucial for safety-critical industries. It overlaps with the “see something, say something” ethos: when psychological safety is present, a junior engineer can question a flawed design, or a crane operator can refuse an unsafe lift, confident that the organisation will value their speaking up rather than punish them. Fostering this climate requires management to respond to reports gratefully and proactively, never with dismissive attitudes. Many UK firms conduct safety climate surveys to gauge how free employees feel to report issues. The benefits extend beyond accident prevention – such openness can improve overall communication and trust within the company. As an example of positive culture, ACCO’s safety audits evolved from mere compliance checks to candid conversations with workers about safety issues, which helped engage staff in solutions rather than alienating them. The result of these cultural efforts is tangible: organisations with strong safety culture have significantly lower accident rates, as people at all levels continuously look out for hazards and for each other. The HSE itself has long emphasized that effective management of health and safety relies on leadership and worker involvement – a message echoed in initiatives like the “Health and Safety Executive’s Leadership and Worker Involvement Toolkit” for construction.

Learning from Tragedies and Near Misses: Part of the cultural shift has been learning-oriented rather than blame-oriented responses when things go wrong. UK businesses increasingly treat accidents as a failure of systems, not just individual negligence. This approach was cemented by legal changes like the Corporate Manslaughter and Corporate Homicide Act 2007, which holds organisations (not just individual workers) liable for fatal accidents caused by management failures. Facing severe penalties, companies became more motivated to instil robust safety governance. High-profile prosecutions and fines in construction – for example, against firms after crane collapses or fatal falls – sent a clear message that safety negligence is unacceptable in modern Britain. Conversely, companies have found that empowering workers and promoting transparency pays off. A case in point is the Crossrail project (one of Europe’s largest construction projects in the 2010s), which adopted a “Target Zero” safety program and encouraged a reporting culture; Crossrail achieved an accident frequency rate far below the industry average and completed tunnelling with an exemplary safety record, demonstrating that even huge, complex projects can be delivered safely with the right culture. The concept of “safety as a value” – meaning it is never compromised for cost or schedule – became a common refrain in the industry. Senior leaders started each meeting with a “safety moment” or briefing, and project managers know that a serious incident could halt work and damage reputations far more than taking the time to do a job safely. In sum, by the 21st century’s first decades, physical health and safety in UK businesses (especially construction) had moved from the margins into the mainstream of management priorities. The next step in this evolution was to expand the very definition of workplace “health and safety” to encompass previously overlooked aspects – notably the mental well-being of workers.

Broadening the Definition of Safety: Mental Well-being and Psychological Health

For many years, “health and safety” in the workplace was interpreted predominantly as protection from physical injuries and illness (the “hard” hazards like machinery, falls, chemicals, etc.). However, a growing body of evidence and advocacy has pushed organisations to recognize mental health and psychological safety as integral to overall workplace safety. In the UK construction sector, this shift has been especially poignant, as the industry confronts a mental health crisis in its ranks that is impacting not only workers’ well-being but also jobsite safety outcomes.

Mental Health as a Safety Issue: It is now well understood that a worker’s mental state can directly affect their risk of an accident. Chronic stress, depression, fatigue, or distraction can impair judgment and focus, potentially leading to mistakes in high-risk environments. A recent industry study by insurer QBE found that nearly 700,000 UK construction workers have suffered injuries due to poor mental health – more than one in five workers in the sector. In that survey, 76% of those who had continued to work while mentally unwell acknowledged that their condition “increases risk of injury.” These figures put hard data behind what safety professionals have long suspected: that ignoring mental health isn’t just a “well-being” issue, but a serious safety problem. Indeed, the HSE has begun treating work-related stress and mental health risks with the same urgency as physical hazards. In 2024 the HSE confirmed it had active investigations into organisational failings in managing mental health risks, signaling that employers may be held accountable under H&S law for widespread stress-related issues. The HSE’s rationale is clear – work-related stress, depression and anxiety account for half of all work-related ill health cases in the UK , and 17 million working days lost annually – an epidemic that cannot be separated from “safety” when poor mental health can result in workers not following safe practices or even resorting to harmful coping mechanisms (like substance abuse) that elevate risk. As one analysis noted, there is a “knock-on safety impact” of employees suffering poor mental health: they may be less likely to adhere to established safe working procedures, with potentially serious consequences in high-risk environments. In short, safety now encompasses both body and mind.

The Human Cost – Breaking the Silence: The cultural taboo around mental health, especially in male-dominated fields like construction, has historically meant that issues stayed hidden. This has had tragic results. Statistics reveal that UK construction workers are significantly more likely to die by suicide than the average person. In England and Wales, 589 construction tradespeople died by suicide in 2020, nearly two every day . Mates in Mind, a construction mental health charity, reports that construction workers have a suicide risk 3.7 times higher than the national average . On a per capita basis, about 34 per 100,000 construction workers take their own lives each year – a shocking indicator of mental distress in the sector. These numbers have finally shattered the illusion that mental health is a personal matter separate from workplace safety. UK industry leaders now talk openly about the “silent crisis” of mental health in construction, noting for example that workers in this sector are 63% more likely to die by suicide than the average UK worker. Such data has been a wake-up call: just as the Victorian public was horrified by physical fatalities among workers, today’s public and workforce are increasingly cognizant of psychological harm. As Rebecca Thompson, former president of the Chartered Institute of Building, observed, until recently “the industry has not treated mental health with much urgency. Compared with the laudable zero harm culture now commonplace on site, there was a marked contrast in attention paid to well-being.” This is now changing rapidly.

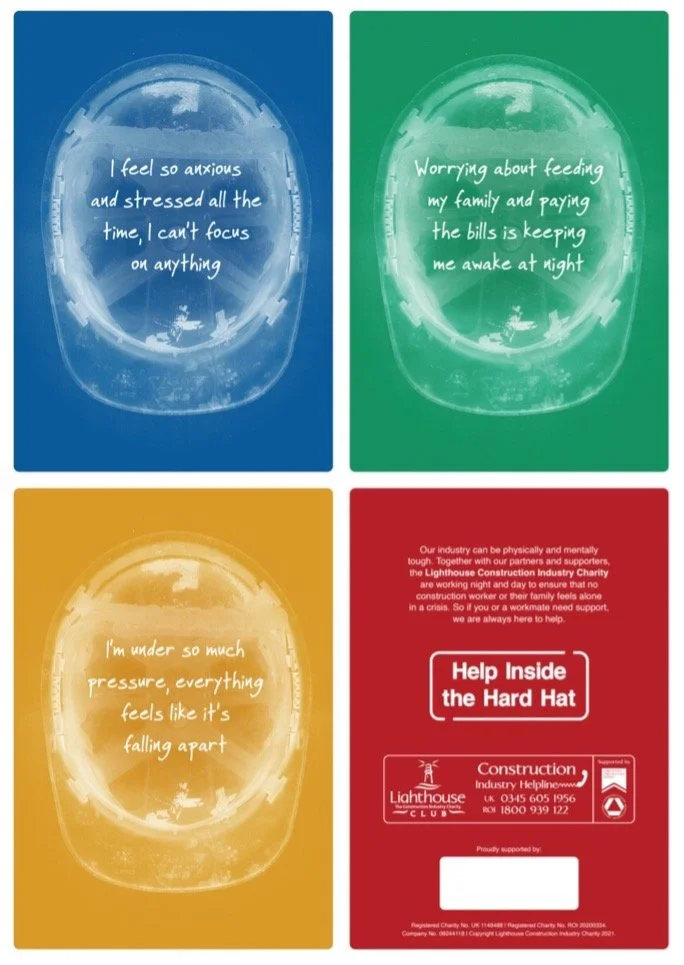

“Help Inside the Hard Hat” awareness posters displayed at a UK construction site (Lighthouse Club campaign).

Initiatives for Mental Well-being: In the past 5-10 years, a surge of initiatives has emerged in UK construction and broader business to address mental well-being as part of safety culture. One prominent example is the “Mates in Mind” program (launched in 2017 by the British Safety Council and partners), which provides awareness training, resources, and support networks in construction companies. Many construction firms have introduced mental health first aiders on sites – trained individuals whom workers can approach for initial support, much as one would go to a first aider for a physical injury. The Lighthouse Club, a construction charity, launched the “Help Inside the Hard Hat” campaign in 2021-2023, using posters and on-site events to raise awareness that help is available and it’s okay to talk about mental struggles. This campaign prominently advertises that in the UK, “two construction workers take their life every working day,” urging workers and employers alike to “stop the stigma” and seek support. The campaign’s brightly coloured posters – displayed on site hoardings – list helpline numbers and drive home the message that mental health is as important as physical safety on the job.

Companies themselves are also investing in mental well-being programs. It’s becoming common for organisations to offer Employee Assistance Programs (EAPs) that include counselling services, stress management workshops, and financial or legal advice (since external stressors like money problems can affect mental health). Some construction firms have implemented regular “toolbox talks” on mental health – brief, informal chats on site where supervisors remind crews about resources and encourage looking out for one another’s mood and stress levels, just as they would look out for physical hazards. Leading by example, senior executives have begun sharing their own experiences with stress or burnout to destigmatize these topics. On the policy side, new guidelines like ISO 45003:2021 were introduced as the first global standard on psychological health and safety at work, providing a framework for managing psychosocial risks within occupational health and safety systems. The existence of ISO 45003 underscores the formal acceptance that mental health is a key aspect of workplace safety management. Additionally, the HSE has launched campaigns on work-related stress and even signalled willingness to prosecute extreme cases of negligence in protecting mental health.

Integrating Mental and Physical Safety: Organisations are increasingly integrating mental well-being metrics into their overall safety dashboards. For instance, they track not just injury frequency rates but also indicators like stress-related absence rates or employee survey scores on well-being. The rationale is that high stress environments are likely to have more accidents, and conversely, a supportive work environment yields both better morale and safer behaviour. A 2023 analysis noted that the UK had 900,000 cases of work-related stress, depression or anxiety in 2022/23, far dwarfing the 135 fatal accidents that same year. Forward-thinking companies see those 900k cases as preventable harm that a robust safety culture must tackle. Construction firms have responded by adjusting work practices – for example, trying to mitigate extreme overtime and fatigue on projects, providing decent welfare facilities on sites (quiet break areas, mental health signage, private phone booths to call support lines, etc.), and training managers to recognize signs of mental distress (such as sudden drops in performance or attendance). Some have instituted policies that encourage taking regular leave and discourage the old macho culture of “toughing it out.” These efforts are often bundled under the banner of “Health, Safety and Well-being” – an evolution of the traditional H&S department to explicitly include mental wellness. The results are promising: many companies report reductions in sickness absence and improvements in staff retention when they actively address mental health. Moreover, when workers feel genuinely cared for, their engagement with safety initiatives rises; they are more likely to follow rules and less likely to take dangerous shortcuts because the overall culture is one of mutual respect and care.

Psychological Safety and Trust: Alongside mental health support, the concept of psychological safety at work (pioneered by Harvard’s research and popularised via case studies like Google’s Project Aristotle) has gained traction in the UK. Psychological safety here refers to team dynamics – ensuring that employees feel safe to voice opinions, admit errors, and challenge practices without being embarrassed or punished. This overlaps with safety culture: a team with high psychological safety is more likely to confess, for example, “I almost slipped off that scaffold yesterday because the planks were loose,” which allows the team to fix the issue and learn, rather than hiding it out of fear. Organisations are training leaders to adopt a coaching mindset rather than a fault-finding one. The old foreman’s style of yelling at a worker who erred is being replaced with a more constructive approach – investigating what factors led to the error and how the system can prevent it, rather than simply blaming the individual. This approach not only improves morale and learning, but also aligns with legal trends: under the 1974 Act and subsequent laws, employers have a broad responsibility, so it’s often the system that is accountable in any case. Many companies explicitly include psychological safety as a goal in their safety strategy. For example, they might measure the percentage of employees who agree with the statement “I feel comfortable stopping work if I perceive a hazard” or “Management genuinely listens to safety concerns” in anonymous surveys. High positive responses correlate with fewer incidents because problems are addressed early.

In sum, the definition of workplace safety in Britain has evolved to treat mental well-being on par with physical safety. This means that a truly “safe” organisation is one that protects people from accidents and occupational diseases and from chronic stress, bullying, or psychological harm. It also means recognising that mental distress can be both a consequence of work and a contributing cause of accidents. UK businesses, especially construction firms, are adapting by embedding mental health into their safety culture through open communication, support mechanisms, training, and leadership example. The result is a more holistic view of “health and safety” – aligning with the World Health Organization’s broad definition of health as complete physical, mental and social well-being.

The Third Evolution: Cyber Safety as a Shared Responsibility

As safety culture matures, organisations are discovering a new frontier of risk that requires the same all-hands-on-deck approach: cybersecurity and fraud prevention. With businesses increasingly digital and interconnected, cyber risks (data breaches, phishing scams, ransomware attacks, etc.) have the potential to disrupt operations, cause financial loss, and even endanger physical safety (for example, if industrial control systems are hacked). In recent years, British companies have begun to treat “cyber safety” as everyone’s responsibility, much like traditional workplace safety. In effect, cyber awareness is becoming the third pillar of safety culture alongside physical safety and mental well-being.

Why Cybersecurity is a Cultural Issue: It might initially seem that cybersecurity is purely a technical domain for the IT department. However, it has become evident that human behaviour is a critical factor in most cyber incidents. According to analysis of UK data breaches reported to the Information Commissioner’s Office, “90% of cyber data breaches [are] caused by user error.” These errors range from clicking on phishing emails, using weak passwords, losing laptops, to misconfiguring systems – mistakes that technology alone cannot prevent. In one sense, this is analogous to safety: just as the best machinery guards or safety protocols fail if workers bypass them, the best firewalls and anti-virus software fail if an employee unknowingly lets the attacker in. Recognising this, organisations and government bodies have been calling for a shift in mindset: cybersecurity is not just an IT issue, but a “shared responsibility” of every employee. The UK’s National Cyber Security Centre (NCSC) bluntly states that a “positive cyber security culture is essential because it’s people that make an organisation secure, not just technology and processes.”. In practice, this means cultivating habits and awareness among staff so that they consistently act in ways that protect information and systems – akin to how we cultivate safe habits on a construction site.

Parallels with Physical Safety Culture: Cyber safety culture borrows many concepts from conventional safety culture. For example: Leadership commitment – just as executives must lead on safety, they also need to champion cybersecurity (e.g. by following policies themselves and prioritizing investments in security training and tools). Training and drills – companies conduct regular cybersecurity awareness training, much like safety training. Employees might attend sessions on how to spot phishing emails or participate in phishing simulation exercises where fake scam emails are sent to test their vigilance. Reporting “near misses” – employees are encouraged to report suspicious emails or potential security incidents immediately, without fear. In fact, many firms set up easy reporting (one-click buttons in email clients to report phishing) and reward employees for alerting IT to phishing attempts. This mirrors the “see something, say something” approach: if an employee accidentally clicks a bad link, the culture should make them feel safe to report it at once so damage can be mitigated, rather than staying silent out of embarrassment (which could make things worse). Forward-leaning organisations explicitly promote a no-blame culture for cyber incidents, focusing on learning and improving defences rather than punishing the individual who was duped – similar to how progressive safety culture treats an accident as an opportunity to strengthen the system. Shared vigilance – employees are taught that basic cyber hygiene (using strong passwords, not tailgating someone through secure doors, keeping software updated) is part of their daily responsibility, just as wearing PPE or locking out equipment would be. In meetings or internal newsletters, companies now include “cyber safety moments” analogous to safety moments, where a recent cyber threat or scam is discussed, and everyone is reminded of best practices.

Case Studies in Cyber Training: Many UK businesses have launched comprehensive cybersecurity awareness programs in the last decade. One case study is a global manufacturing company that implemented enterprise-wide security awareness training in multiple languages; as a result, it saw the percentage of employees failing phishing email tests drop from 35% to under 15% – a more than 20% improvement in phishing resilience. Another example is Credit Suisse (with large operations in London) which rolled out an engaging cyber training platform to over 86,000 employees globally, significantly boosting participation and measurable security behaviours. Likewise, the Hastings Group (a UK insurer) adopted a human-centric cyber training approach to build a “culture of resilience” rather than mere compliance. The UK government, via the NCSC, has even made a free e-learning module (“Stay Safe Online: Top Tips for Staff”) available to all organisations, underlining that cyber awareness is as basic and vital as any safety induction. These programs cover topics like phishing detection, secure use of passwords and devices, and incident reporting. When Cool Waters Cyber was asked to manage the cyber security for the National Highways A303 Stonehenge Bypass construction project, an integrated approach to Safety was part of the strategy they developed. Mark Faithfull served as the CISO for the project: “We developed an approach that embraced safety in all its facets – physical safety, mental wellness and cyber safety. It was all just safety and proposed an integrating reporting mechanism and cultural adoption. For example, safety moments in project meetings would encompass any of the three aspects – physical, mental or cyber.”

Metrics from such initiatives are encouraging. A 2023 Aviva survey found that 89% of employees rated their company’s cybersecurity as strong, but paradoxically only half could identify basic measures like phishing reporting, revealing a gap in awareness. With training, these awareness levels are rising. Companies report improvements not only in reduced security incidents but also in employee confidence: after training, staff feel more empowered as the “first line of defence” and take pride in catching cyber threats. As Aviva’s head of cyber noted, “employees are the first and most important line of defence against cybersecurity incidents, so awareness and engagement are vital”. He emphasized that building a “cyber resilient culture requires board-level commitment” and continuous investment in training and resources – essentially echoing the exact principles long applied to physical safety. Just as a safety culture must be nurtured daily, a cyber safety culture needs regular reinforcement (for example, monthly security newsletters, gamified challenges, recognition for departments with good security practices, etc.).

Enterprise-wide Protocols and Shared Tools: Organisations are integrating cyber safety into their standard operating procedures. For instance, many companies now include cybersecurity tips in their routine safety briefings or meetings. It’s not unusual on a construction site for a morning huddle to conclude with a reminder like, “And remember to be vigilant with any emails you get – we’ve seen a fake invoice email circulating, so double-check sender addresses. If you see something off, report it to IT.” In office environments, companies conduct “cyber drills” akin to fire drills – simulating a breach scenario to practice response. This drives home that reacting to a cyber incident is a team effort, not solely IT’s job. Another development is integrated reporting systems: modern incident management software often allows employees to log not just H&S incidents but also information security incidents. For example, an employee might use one reporting portal to report a near-miss injury or to report a phishing attempt – both viewed as protecting the organisation. Some firms have combined their Health & Safety committee with Information Security into a broader Risk or Safety Committee, ensuring cross-pollination of ideas and a unified strategy.

Real-world Consequences: The push for cyber awareness isn’t just theoretical. Real incidents have underscored the stakes. The infamous 2017 WannaCry ransomware attack, which crippled parts of the UK’s National Health Service, showed that a lack of cyber preparedness (unpatched systems, slow incident response) can literally put lives at risk by disrupting healthcare delivery. In the private sector, breaches like the 2015 TalkTalk hack (which exposed customer data and led to a large fine and reputational damage) prompted companies across Britain to strengthen their internal training and phishing defences. Likewise, construction and engineering firms, which increasingly rely on digital models and remote site connectivity, have been targets of cyberattacks; companies such as Balfour Beatty have publicly discussed ramping up employee cyber education after attempted intrusions. The concept of “cyber hygiene” is often promoted alongside personal safety and health hygiene. For example, just as workers are taught to maintain a tidy worksite to prevent trips, they are taught to maintain a “tidy digital workspace” – e.g., not writing passwords on sticky notes, locking their computer when away, and being cautious with USB drives.

Government and industry bodies also reinforce this third pillar of safety. The UK’s annual Cyber Security Breaches Survey reports on how businesses are faring; in 2024 it found that 50% of businesses had identified a cyber breach or attack in the past year, illustrating how common the threat is. It also noted that only about 1 in 5 businesses train staff monthly on cyber, which suggests room for improvement in making it an ongoing effort. To address this, October has been designated Cybersecurity Awareness Month (an international campaign), and many British firms partake by having special events and refreshers each year during that month. The messaging closely mirrors safety week campaigns – emphasizing personal responsibility, awareness of others, and learning from past incidents.

In summary, cyber safety has emerged as the “third evolution” of workplace safety culture. Starting with physical safety, expanding to mental health, and now encompassing digital security, the trajectory shows an ever-widening scope of what it means to keep a business and its people safe. The same fundamental ethos applies: success depends on engaging everyone in the organisation. The lessons learned from decades of improving on-site safety – strong leadership, clear policies, regular training, open communication, and empowered employees – are being applied to cyber risk. Companies that once might have left security to a small IT team now realise that every employee, from the CEO to the newest apprentice, has a role in maintaining “safety” in the cyber realm.

Toward a Holistic Safety Culture – Integrating Physical, Mental, and Cyber Safety

The evolution of safety culture in British business – especially evident in construction – illustrates a clear trend: a broadening and deepening of what ‘safety’ means, coupled with a more holistic, people-centric approach to managing risk. Physical safety, mental well-being, and cybersecurity may seem like separate domains, but they share common principles and, increasingly, common implementation strategies. This raises an important question: should these aspects be integrated under a unified safety approach? The research and cases discussed suggest that the answer is yes – organisations stand to gain significantly from breaking down silos and treating safety in a comprehensive manner.

Benefits of an Integrated Approach: Integrating physical, mental, and cyber safety under one umbrella of “total safety” can lead to more consistent messaging, efficient use of resources, and a stronger overall culture. All three aspects ultimately concern protecting employees and the organisation from harm. When treated together, it reinforces the idea that safety is everyone’s responsibility everywhere – whether wearing a hard hat, speaking up about feeling overwhelmed, or being cautious with a suspicious email. A unified approach ensures no aspect is neglected; for example, a weekly safety briefing can touch on a jobsite hazard, remind teams to check on each other’s stress levels during a big project push, and mention a current phishing scam to watch out for. This keeps safety multifaceted and front-of-mind. Many companies are already heading this direction, rebranding their departments as “Health, Safety, Security and Well-being” or similar. In construction, it is not uncommon now to have a “Safety, Health and Environment (SHE) Director” who also liaises with IT security on overlapping concerns (such as protecting the safety of connected industrial equipment). A holistic safety culture also helps break the mentality of compliance for compliance’s sake. Instead of employees feeling “oh, another training”, they see the bigger picture that all these trainings – whether on hazard spotting, mental health awareness, or data protection – are part of the same mission to keep themselves and the business safe. This can improve engagement, as people who might otherwise tune out “IT stuff” or “HR stuff” realise it’s all safety stuff.

Practical Steps for Organisations: To implement a more holistic safety culture, businesses can take several steps:

Unified Governance: Consider establishing a cross-functional safety committee that includes HSE managers, HR/Well-being leads, and IT security leads. This committee can oversee policies and campaigns that cover all safety dimensions, ensuring consistent priority and messaging. Some organisations create an executive role (e.g. Chief Safety Officer or Chief Risk Officer) whose remit spans physical safety, health, and information security, to drive integration from the top.

Holistic Training and Induction: Update training programs and inductions to cover physical, mental, and cyber risks side by side. For instance, a new hire orientation can include: how to report a work hazard or injury, how to access mental health support, and how to maintain cyber hygiene. By bundling these, the employee immediately sees that the company values all aspects of their well-being and expects their participation in each. Modular training can still provide depth in each area, but an overarching “safety first” theme ties them together. Some companies have started “Safety & Security” days where they combine activities like safety drills, wellness workshops (e.g. mindfulness or fatigue management), and cybersecurity games into one event, emphasising the interrelated nature of these topics.

Integrated Reporting Systems: Implement or modify reporting mechanisms so that employees have a one-stop shop to report any type of safety concern – be it an unsafe condition, a near-miss, a colleague showing signs of stress, or a suspected phishing email. Modern incident management software can categorize reports, but having one portal/app lowers barriers to reporting and signals that the company views them all as important. On the back end, the safety/HR/IT teams can triage appropriately. Integrated data can also allow new insights, such as correlating high-stress periods with incident spikes or identifying if certain teams need extra cybersecurity focus. Companies like BT Group have reported success in integrating security incident reporting with their general incident reporting, which increased reports of near-miss cyber incidents (like caught phishing attempts) similar to near-miss accident reporting.

Comprehensive Safety Briefings: Evolve the routine of safety briefings or “toolbox talks” to encompass a broader range of topics. For example, a daily briefing might start with a physical safety tip (e.g. ladder safety), then a quick mental health check-in (“Reminder: it’s been a busy week, take time to rest this weekend; our employee helpline is there if you need to talk”), and end with a cybersecurity tip (“Don’t forget to update your work iPad – patches were released yesterday”). Keeping each point brief ensures the meetings aren’t much longer than usual, but the impact is employees gradually internalize that safety is multi-dimensional. Larger meetings (monthly all-hands or departmental meetings) can include a short “Safety moment” covering any of the three pillars – perhaps cycling through them. Leadership can also share balanced scorecards that include metrics from all areas (e.g. “0 lost-time injuries this quarter, 2 mental health leave cases (all supported back to work), 1 minor data breach (lessons learned)”). This integrated reporting to staff prevents the silo mentality and demonstrates equal seriousness.

Cross-Training and Collaboration: Safety professionals can be cross-trained in basic cybersecurity and mental health first aid, while IT security staff can learn about safety culture practices. This cross-pollination can generate creative approaches. For instance, the concept of a “near-miss” could be borrowed by IT teams to analyze thwarted attacks, and conversely, safety teams might adopt analytics from cybersecurity on human error patterns. Organisations might also merge their communications for these topics – a single newsletter or intranet site for “Safety and Well-being” that covers all issues, rather than separate channels. The language used can reinforce connections, e.g. referring to “safe behaviours” in both context of wearing PPE and using secure passwords.

Challenges and Considerations: While integration has benefits, it should be done thoughtfully. Each domain (physical, mental, cyber) does have its own expertise and regulatory requirements – for example, compliance with cyber/data protection laws is a distinct skill set from HSE law compliance. Thus, an integrated approach works best when it facilitates collaboration but still respects subject matter experts. Care should be taken that one area doesn’t overshadow another; for instance, if a company has had a high-profile cyber incident, it shouldn’t result in traditional safety being neglected in meetings – balance is key. Additionally, employees should not feel overloaded by “safety everything”; communication should remain clear that these efforts are for their benefit, not just corporate box-ticking. Maintaining a positive, supportive tone is important, especially around mental health (avoiding any implication that employees are “risks” if they are struggling – the focus must be on support and prevention).

Global and Future Outlook: The holistic approach to safety is aligning with international trends. The U.S. NIOSH “Total Worker Health” program, for example, integrates occupational safety with health promotion, recognizing that worker well-being is multifaceted. Many European companies too are expanding the mandate of safety committees to include psychosocial risks, and cybersecurity awareness is a worldwide movement. By integrating cyber, the UK is somewhat ahead in acknowledging that digital risks require cultural solutions. As industries adopt more technology (think smart construction sites, Industry 4.0 factories), the lines between physical and cyber safety blur (a cyberattack could disable safety systems, for instance). This further argues for unified oversight. It’s conceivable that in the near future, safety professionals will routinely have basic cybersecurity knowledge and vice versa, and companies will develop “Safety & Security” management systems that get audited just like ISO 45001 (safety) or ISO 27001 (information security) are today.

Expert Opinion: Experts generally support an integrated safety approach. Occupational psychologists point out that safety is about creating the right climate and behaviours, regardless of the specific risk; thus one culture can and should encompass all risks. Cybersecurity experts often emphasize the need to borrow from safety culture to address the human element in security breaches. Meanwhile, HSE officials have started talking about “health” in H&S to explicitly include mental health, blurring the distinction between safety and well-being management.

In conclusion, the journey of safety culture in British business – from Victorian construction sites where death was routine, to modern projects striving for zero harm – shows how far we have come in valuing human life and well-being at work. The hypothesis that health and safety have moved from a fringe concern to a fundamental value is strongly supported by the historical trends and current practices. What was once mainly about physical hazards now rightly encompasses psychological health and digital security, reflecting the complex challenges of the 21st-century workplace. Physical safety, mental well-being, and cybersecurity are best seen not as isolated silos but as interconnected strands of an organisation’s overall safety fabric. Adopting a unified approach, with integrated policies, reporting, and a culture that promotes safety in all its forms, can make businesses more resilient, employees more engaged and protected, and ultimately lead to better performance on all fronts. As British businesses continue to innovate in this direction, they set an example internationally: demonstrating that caring for people – whether guarding their bodies, minds, or data – is at the heart of sustainable and responsible business success.

How we can help

Developing a Cyber Safety Culture in Construction

The construction sector has made significant strides in fostering a strong physical safety culture, with rigorous policies, training, and risk management practices that have saved countless lives. The evolution of mental well-being into a core component of workplace safety has further enhanced employee welfare and productivity. However, the next frontier in construction safety is ensuring that cybersecurity is given the same priority as physical and mental safety.

At Cool Waters Cyber, we specialise in helping construction firms develop a proactive cyber safety culture, embedding cybersecurity awareness and best practices into daily operations—just as businesses already do with PPE, mental health initiatives, and site safety protocols. Our approach is practical, hands-on, and designed specifically for high-risk environments like construction, where digital threats can disrupt operations, compromise data, and even endanger physical safety.

Building Cyber Safety into Everyday Construction Practices

To integrate cyber safety into an organisation’s culture, businesses must go beyond compliance checkboxes and isolated IT training. Instead, we advocate for a structured, behaviour-driven approach that mirrors the success of physical and mental health safety campaigns. Below are actionable steps construction firms can take—and where Cool Waters Cyber and Cyber Coach can help:

1. Leadership-Driven Cyber Safety Culture

What to do:

Treat cybersecurity as a business risk, not just an IT issue—making it a leadership priority.

Senior management should regularly discuss cyber safety alongside traditional safety concerns in meetings, reinforcing that everyone has a role to play.

Implement a “Cyber Safety Moment” in daily briefings, toolbox talks, or leadership meetings—similar to physical and mental safety moments—to keep cybersecurity at the forefront.

How we help:

Cool Waters Cyber works directly with leadership teams to assess cyber risks, develop strategy, and embed cyber safety into corporate governance.

We provide executive cyber safety training, helping construction leaders understand cyber risks in practical terms.

2. Empowering Employees with Cyber Awareness and Training

What to do:

Train employees at all levels on common cyber threats such as phishing, credential theft, and invoice fraud—risks that construction businesses face daily.

Ensure employees understand their role in cybersecurity just as they do in physical safety, making cyber safety second nature in daily tasks.

Use real-world construction case studies of cyber incidents to demonstrate risk impact and foster engagement.

How we help:

Cool Waters Cyber provides tailored cybersecurity training for construction teams—delivered in short, engaging sessions designed for site workers, office staff, and leadership alike.

We create custom phishing simulations, testing and improving employees’ ability to spot suspicious emails and scams.

We offer interactive cyber safety workshops that blend online and in-person training, ensuring teams gain practical skills, not just theoretical knowledge.

3. Reporting Cyber Incidents Just Like Safety Incidents

What to do:

Encourage open reporting of cyber threats and near misses (e.g. a phishing email received but not clicked) without fear of punishment, just as near-miss reporting is used in traditional safety culture.

Provide a simple, accessible reporting mechanism, such as a one-click button in email systems to report phishing attempts or a central cyber safety hotline.

How we help:

Cool Waters Cyber can implement (cyber) safety incident reporting tools that integrate with existing safety management systems, streamlining the process for employees.

We help businesses adopt a no-blame cyber safety culture, training managers to handle reports constructively and focusing on learning from incidents.

4. Protecting Supply Chains and Third-Party Risks

What to do:

Ensure all subcontractors, suppliers, and partners adhere to strong cybersecurity policies, just as they must comply with physical health and safety regulations.

Conduct regular cybersecurity audits of digital tools used on construction sites, including BIM (Building Information Modelling) software, IoT devices, and project management systems.

How we help:

Cool Waters Cyber provides supply chain risk assessments, ensuring third-party vendors follow best cybersecurity practices.

We help businesses implement cyber safety standards in contracts with suppliers and subcontractors, reducing exposure to third-party risks.

5. Secure Digital Tools for a Modern Construction Environment

What to do:

Ensure all mobile devices, tablets, and laptops used on-site are securely configured and regularly updated.

Promote strong password policies and implement multi-factor authentication (MFA) for key business applications.

Educate employees on the dangers of shadow IT (unapproved apps or file-sharing tools that increase risk exposure).

How we help:

Cool Waters Cyber offers construction-specific cybersecurity solutions, securing mobile and cloud-based tools used for digital project management, document sharing, and remote access.

We provide penetration testing and risk assessments, ensuring that networks, devices, and applications meet strong security standards.

6. Aligning Cyber Safety with Compliance and Regulations

What to do:

Keep up to date with cybersecurity regulatory requirements in construction, such as the UK Cyber Essentials framework, GDPR (for data protection), and ISO 27001 (for information security management).

Embed cybersecurity into H&S compliance audits and project risk assessments, treating digital threats as part of overall safety governance.

How we help:

Cool Waters Cyber provides compliance support for Cyber Essentials, IASME Cyber Assurance, and ISO 27001, ensuring construction firms meet legal and industry security standards.

Cyber Coach helps teams understand compliance in practical terms, making cybersecurity rules more accessible and actionable for all employees.

Final Thoughts: Making Cyber Safety an Everyday Habit

Construction companies already excel at managing risk and fostering a safety-first mindset. By extending that mindset to cyber safety, businesses can protect not just people, but also data, financial assets, and reputational integrity.

At Cool Waters Cyber, we work with organisations to develop comprehensive cybersecurity strategies, ensuring they have the right policies, tools, and training in place to protect their business from evolving cyber threats.

At Cyber Coach, we help employees at all levels become cyber-aware and cyber-smart, delivering practical, engaging training that makes cyber safety an integrated part of everyday working life—just like wearing PPE or reporting hazards on-site.

By treating physical safety, mental well-being, and cyber security as part of a unified safety culture, construction firms can create a safer, stronger, and more resilient workforce.

Contact Cool Waters Cyber (www.cool-waters.co.uk) for expert cybersecurity strategy & risk management and engaging real-world cyber safety training.

Arrange a free conversation with a cyber expert today: